|

|

| Influencing juvenile justice architecture |

| By Patrick M. Sullivan, FAIA |

| Published: 03/26/2007 |

Editor's Note: Last week, guest writer Patrick Sullivan wrote about the formation and early history of juvenile facilities. In his final part this week, he discusses how facilities have evolved to what they are today.

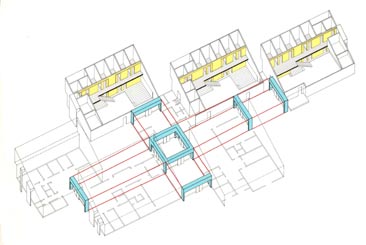

Editor's Note: Last week, guest writer Patrick Sullivan wrote about the formation and early history of juvenile facilities. In his final part this week, he discusses how facilities have evolved to what they are today.After World War II, new facilities included camps for the treatment of juvenile delinquents, which possessed special advantages for housing and treating youth in a non secure environment. They were treatment oriented, and the juvenile was removed from the context of their existing environment. Therefore, it was easier to focus on the group or individual treatment plan, and the open camp atmosphere eliminated most of the stigma attached to “juvy-hall” institutions. Lyman Reform School for Boys Westborough, Massachusetts  Major Changes Correctional facilities, especially those used to support juvenile rehabilitation programs, radically changed during the 1960s. The politics of social upheaval in America during the 1960s and 1970s must be noted because of the revolutionized public attitudes toward juvenile rehabilitation as well as a renewed commitment to social responsibility.(5) The prison reforms of the 1960s that lead to direct supervision and new generation jail design was the catalyst for creative treatment approaches and new buildings for the incarcerated. At the same time the legislation of the 1960s and 1970s created a search for new designs and treatment programs that lead to a deinstitutionalization of custody facilities.(6) As a result, the Federal Bureau of Prisons created a new building form and operational approach termed “new generation.” “New generation” refers to new or remodeled correctional facilities designed with a direct supervision inmate management orientation. A “pod” or “podular design” defines a group or living unit in a correctional facility, the old cell-block. The pod contains sleeping rooms (cells), hygiene facilities, a common dayroom, and smaller spaces for education, counseling, or related activities, staff areas, storage and, in some buildings, dining space. Recreational areas are nearby. The living unit or pod can be any level of security (i.e., maximum, medium, or minimum). Its approach was based on common-sense principles and the normalization treatment model which sought to manage human behavior positively, consistently and fairly. The facility as a whole sends a message. If the building, a jail or juvenile hall, in its design and management style, expects people to act uncivilized, it will evoke that behavior. If the message is that antisocial behavior is inappropriate, the majority will conform to that message. Most residents want to avoid trouble and will do so if given a chance. The few who create problems, five to 10 percent, are separated from the majority. Direct supervision is created by an appropriate number of staff members who are located in the pod with the detainees 24 hours a day. The appropriate number of supervisors and counselors has never been definitively decided; however, offender groups less than 10 or 12 are small and more than 24 are too big in juvenile facilities; more than 50 in jail and prison units are too big. Ariel view of King facility in Seattle, WA  Changes in Rights of Minors The juvenile court functioned for nearly 70 years with little constitutional oversight and without the required presence of lawyers. Also, the juvenile justice process was largely untouched by the early phase of the Warren Court revolution that transformed criminal procedure. In the 1960s both the courts and society had to deal with growing questions about the continued validity and vitality of the juvenile court's informality and treatment focus in the absence of full regard for due process. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the fundamental fairness of the juvenile court's process in a case from the District of Columbia, Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541, 1966. The Court concluded that Morris Kent was denied his due process and statutory rights when the trial judge failed to hold a hearing prior to transferring the 16-year-old to the adult court for trial and did not give Kent's lawyer access to the social information relied upon by the court. Dayrooms at the King facility   Since 1967, court decisions have changed juvenile court procedures and practices. The Gault decision affirmed that juveniles have the right to due process and marked the constitutional domestication of the process model. Additional court findings began to recognize the rights of juveniles. The decisions in the Escobedo and Miranda cases stated that constitutional rights apply to juvenile courts. Although the 1971 McKeiver case held that due process does not require a jury trial in juvenile proceedings, rights like having counsel in cases where incarceration might result (the right to confront and cross-examine witnesses and the privilege against self-incrimination) do apply in some juvenile court situations. More Changes In early 1971, Massachusetts sent a definitive message to the rest of the nation by closing all of its state training schools. The Lyman School, the first training school in America, was the first to be closed. In a series of events, Massachusetts replaced its large traditional juvenile institutions with a network of small secure facilities and a wide array of community-based services. Almost 1,000 youth were removed from outdated institutions. The reforms met with intense opposition by the corrections establishment. Youth advocates used the Massachusetts model to draft the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) of 1974. This offered grants to states willing to remove status offenders from secure custody, separate adult and juvenile inmates, and promote advanced juvenile justice practices. However, only Utah, Vermont, and Missouri attempted to replicate the Massachusetts approach. Title III of the JJDPA encourages the establishment of temporary, non-secure shelter care facilities for runaway youth and prompt reconciliation with parents. The act supported the development of community-based alternatives to the institutionalization of nonviolent and non dangerous delinquent youth. Political Backlash In the late seventies, the reform initiative of the JJDPA was not supported by contemporary political attitudes that fundamentally opposed the concept of deinstitutionalization and community-based treatment. Through most of the 1980s and 1990s, the public response to juvenile offenders was decidedly unsympathetic. This period witnessed legislative reforms designed to make it easier to adjudicate youngsters in adult courts. States mandated an automatic waiver to the criminal justice system for a new range of offenses. A national war against drugs produced an unprecedented increase in youngsters entering adult penal facilities. Georgia, Colorado, and Minnesota passed laws permitting juvenile correctional officials broad latitude in administratively transferring young people to “youthful offender” facilities operated by adult corrections departments. Juvenile facilities faced severe crowding, especially in detention centers. Lengths of stay increased steadily from 1980 to 1995. Despite the expanded use of incarceration, public officials did not invest in new facilities nor were agency budgets increased. During the late 1990s many states and local agencies faced lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of confinement conditions in the jurisdictions juvenile facilities. History Repeating During the early1990s, federal funds were made available for boot camps similar to the early 1900s military drill exercises. Delinquents were confined in adult institutions and overcrowding was so pronounced that lawsuits were brought against jurisdictions to close facilities. Isometric of San Luis Obispo, California facility  During these “get tough” times, lessons of the past were not abandoned though. Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Arizona, Nebraska and Indiana began positive steps to eliminate large institutions and embrace the ideas of local community-based treatment centers. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention's (OJJDP) “Comprehensive Strategy on Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders” placed a major focus on blending treatment and public safety concerns. Professional groups like the American Correctional Association, the American Probation and Parole Association, and the National Juvenile Detention Association were speaking out against the policies that relegated juveniles to adult jails. San Luis Obispo facility  Architectural Change The real stimulus for architectural change was the Juvenile Crime Enforcement and Accountability Challenge Grant program of 1997, amended in 1998, which created matching Federal funds for new and remodeled juvenile facilities. It encouraged states to provide direct intervention strategies, for both male and female offenders, and emphasized strategies related to out-of-home placement for low risk juveniles. The Challenge Grant program strongly endorsed the collaboration among the juvenile justice system and community-based programs and required development of new demonstration projects and architectural responses for at-risk juveniles. Large congregate-care juvenile facilities have not proven to be effective in the rehabilitation of the juvenile offender. The most recent approaches and most effective strategy for treating and rehabilitating juvenile offenders is a comprehensive, community-base model that integrates prevention programming -- a continuum of pretrial and sentencing placement options, services, graduated sanctions, and after care programs. This approach reserves secure placement for only the most violent and serious juvenile offenders - those who pose a threat to public safety or themselves. Louis Gossett, Jr. facility, Lansing, NY  Even for jurisdictions under pressure to “get tough” on juvenile crime, planning new facilities within this framework has programmatic, economic, and system wide advantages. Small, community-based or regional facilities can: The spread of diversion plans, including the establishment of Youth Service Bureaus in California, and a system-wide goal to establish numerous centers for community-based treatment programs in Georgia (2000 to 2004) exemplify the attempts to keep dependent children and youth who exhibit minor misbehavior out of the courts. Louis Gossett, Jr. facility  Opinion A community facility can also offer youth enhanced opportunities for independent living. Phased re-entry programs can be created which allow youth and their support networks to participate in a gradual transition into the community. What's next? Perhaps we should be thinking about ways that will help keep children at home with their family, as well as in school, at church and with positive role models. A Summary of Juvenile Facility Design Since the 1800s, juvenile institutions with regard to architectural styles and environments for the support of treatment programs have evolved schematically: (5) It is interesting to compare the similar political and social conditions which existed in the periods between 1850 to 1880, and 1950 to 1980. Both periods experienced high inflation after the Civil War and World War II. The country experienced unprecedented growth, presidential assassinations, great political change and a new way of dealing with housing delinquent children. The reform schools of the 1880s begin to train children for a trade and separated children and adults. Institutions were usually located in rural areas. In the 1970s and 1980s delinquents were placed in new generation, direct supervision settings, the deinstitutionalization of juvenile facilities. A community corrections system was the goal. (6) Residential environments: A deinstitutionalization perspective (Brown and McMillen, 1979) presents a compendium of research and standards on critical architectural issues. It was intended to provide a deinstitutionalization perspective for youth workers, juvenile justice practitioners, architects, elected officials, and citizen advocates interested in the development of juvenile residential programs and normative residential environments. Resources cited: American Correctional Association in cooperation with the Commission on Accreditation for Corrections. (1990 and supplements). Standards for adult correctional institutions, Third Addition, Laurel, MD: Author. American Correction Association in cooperation with the Commission on Accreditation for Corrections. (1991, Supplement 2004). Standards for juvenile detention facilities, Third Edition. Laurel, MD: Author. Beck, A. R. (1999). New generation jails design - A shift away from 200 years of thinking. Kansas City, MO: Justice Concepts Inc. Retrieved on January 13, 2005 from http://justiceconcepts.com/design.htm Brown, J. W., & McMillen, M. J. (1979). Residential environments, a deinstitutionalization perspective. Washington, D.C: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Fabricant, M. (1980). Deinstitutionalizing delinquent youth, the illusion of reform? Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co. Inc. Howell, J. C. (Ed.). (1995). Guide for implementing the comprehensive strategy for serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offender. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Institute of Judicial Administration and American Bar Association. (1977). Standards relating to architecture facilities. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Co. Author. Krisberg, B. (1996). The historical legacy of juvenile corrections, correctional trends, juvenile justice programs and trends. Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association. Krisberg, B., & Howell, J.C. (1998). The impact of juvenile justice system and prospects for graduated sanctions in a comprehensive strategy. In R. Loeber and D.P. Farington (Eds.). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful intervention. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. Krisberg, B., Onek, D., Jones, M., & Schwartz, I. (1993). Juveniles in state custody: Prospects for community-based care of troubled adolescents. San Francisco, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency. Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), (1974). U.S. Department of Justice, Indexed legislative history of the juvenile justice and delinquency prevention act of 1974 ,Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office. Loeber, R., and Farrington, D. P. (Eds.) (1998). Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful intervention (pp314-345). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Institute of Corrections. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Report of the National Advisory Committee for Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, (1980). Standards for the administration of juvenile justice. Washington, D.C: Author Pub.L. 105-277, referencing H.R. 3, Title III, 105th Cong., 1st Sess (1997). Retrieved on November 11, 2005 from Robinson, J. et al. (1984). Towards an architectural definition of normalization: Design principles for housing severely and profoundly retarded adults. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Schwartz, I. M. (1989). (In)Justice for juveniles: Rethinking the best interests of the child. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Shepherd, R. E. Jr., (2003). Still seeking the promise of Gault: Juveniles and the right to counsel. Criminal Justice Magazine 18(3). Retrieved October 19, 2005, from http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/cjmag/18-2shep.htm Sutton, J. R. (1988). Stubborn Children: Controlling Delinquency in the United States, 1640-1981. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Wener, R. E. (2003) (in press). The effectiveness of direct supervision correctional design and management: A review of the literature. Criminal Justice & Behavior. Wolfensberger, W. (1972). The principle of normalization in human services. Toronto, Canada: National Institute on Mental Retardation. Zavlek, S. (2005, August). Planning community-based facilities for violent juvenile offenders as part of a system of graduated sanctions, In Bulletin, Juvenile Justice Practices Series, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

Comments:

Login to let us know what you think

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

cheap herve leger dresses

herve leger dresses on sale

canada goose trillium

herve leger dresses on sale

discount herve leger dresses