|

|

| Practical Perspective: An Action Plan to Achieve Inmate Programming Outcome Measures and Greater Accountability |

| By Major Clifford G. Tebbitt, Jail Administrator, Scott County Sheriff's Office |

| Published: 01/02/2012 |

To facilitate the construct of an action plan, Yukl and Lepsinger (2004) outlines six actionable steps for the planning necessary to advance an inmate programming accountability systemic objectives. Research conducted a number of years ago, but still very valid today regarding what is understood about the flow of change has been very useful in planning organization development interventions and in working with managers to explain and plan for the various challenges that can be expected in implementing change (Kyle, 1993). The kind of “systems encompassing thinking” Yukl and Lepsinger recommend within their action-planning model is key to resolving a noted Acme County problem. The action-planning model applied to this problem initially appeared to guide process in a linear fashion. However, further developed familiarity with the discussed Yukl and Lepsinger action-planning model provides an integrated comprehensive tool to facilitate problem solution when applied.

To facilitate the construct of an action plan, Yukl and Lepsinger (2004) outlines six actionable steps for the planning necessary to advance an inmate programming accountability systemic objectives. Research conducted a number of years ago, but still very valid today regarding what is understood about the flow of change has been very useful in planning organization development interventions and in working with managers to explain and plan for the various challenges that can be expected in implementing change (Kyle, 1993). The kind of “systems encompassing thinking” Yukl and Lepsinger recommend within their action-planning model is key to resolving a noted Acme County problem. The action-planning model applied to this problem initially appeared to guide process in a linear fashion. However, further developed familiarity with the discussed Yukl and Lepsinger action-planning model provides an integrated comprehensive tool to facilitate problem solution when applied.

The objective of this Practical Perspective edition is to identify a project that needs to occur within an organization. Canvassing the many possibilities within my organization, as the Acme County Jail Administrator, I have struggled with the lack of accountability in the area of inmate programming for too many years. The difficulty of connecting values to desires is why so many organizations seem to struggle with their planning processes (Kulisek, 2008). The literature supports the notion that three basic elements lead to the attainment of a desired outcome or objective. Within an organization, the three elements and the outcome are typically something like policy plus strategy and tactical plan is goal attainment (Kulisek, 2008). It especially important at this time to take into full consideration our current economic climate with the many cutbacks and diminishing revenue streams the public sector face today. Our current economic situation sets that pressing conditions for greater inmate programming resources accountability, and demands accurate reporting reflective of the ongoing expenditure authority that has been allocated over the past 4 years. Currently, it is assumed from an evidenced based best practice standpoint, the organization needs to adopt outcome measures to support future resource decision-making and too achieve greater resource accountability. The literature suggest by way of advancing direct and indirect forms of leadership methodology can improve efficiency and process reliability within the area of achieving inmate programming accountability (Yukl & Lepsinger, 2004). Past attempts to introduce accountability has fielded reporting measures that have failed to provide measuring inmate programming effects on recidivism. The challenge is now believed to be one for leadership and management in this organization to establish a course of action that will breakdown the culturally reinforced barriers that have prevented lesser efforts in the past to accomplish resource accountability so desperately needed, as future favorable funding decisions is seen will pivot upon. The foundation in this case is based on a notion that measurement indicators need to be enveloped, a supporting measurement matrix needs to be in place to facilitate data reporting, and organization-transcending needs to occur that supports in-depth inmate programming accountability goals. To facilitate the construct of an action plan, Yukl and Lepsinger (2004) text outlines six actionable steps for the planning necessary to advance an inmate programming accountability systemic objectives. Many managers in the past attempting to address this challenge have touted the concept of "working smarter, not harder," and while that mindset has merit, it can pave the way to omitted details, skipped steps and a lack of diligence that can jeopardize operational quality and safety (Ritzky, 2003). In this environment, the business of proving safe and secure jail services, safety is paramount in the development of any strategy and subsequent action planning intended to improve the enterprise. You might say a well-developed strategic plan simply serves to connect values (or policies) to desired outcomes (or objectives) (Kulisek, 2008). The Flow of Action Planning Research conducted a number of years ago, but still very valid today regarding what is understood about the flow of change has been very useful in planning organization development interventions and in working with managers to explain and plan for the various challenges that can be expected in implementing change (Kyle, 1993). Expanding upon the fundamentals for dealing with basic resistance to change, the flow of change in accordance with Yukl and Lepsinger’s (2004) model involves six key action-planning steps that address operational planning levels with the aim of clarifying roles and objectives. A survey of the literature would suggest critical to addressing the present lack inmate programming resource expenditure accountability the organization must tie time, labor and budget to strategic and operational plans in order to ensure success (Kendrick, 2004). Yukl and Lepsinger’s (2004) model concept of developmental stages within an action planning process is within an organization context, a basic model outline that defines readiness for change in terms of the six stages. In their schematic representation, managers and leaders influence in one of six developmental courses of action:

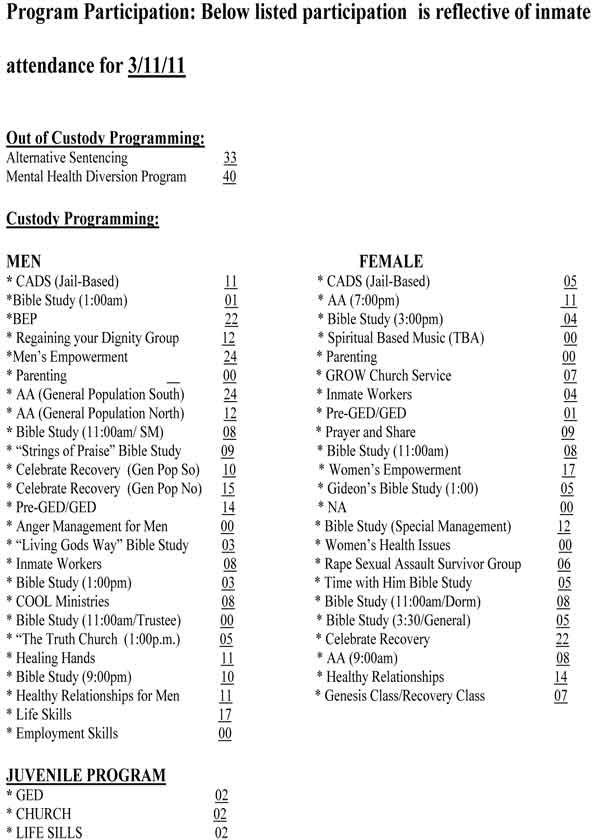

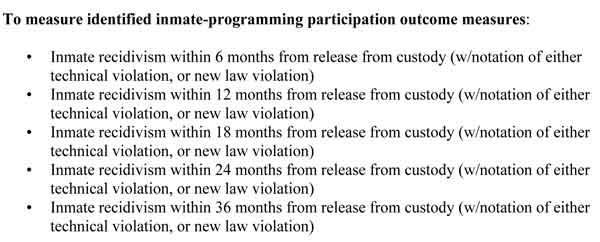

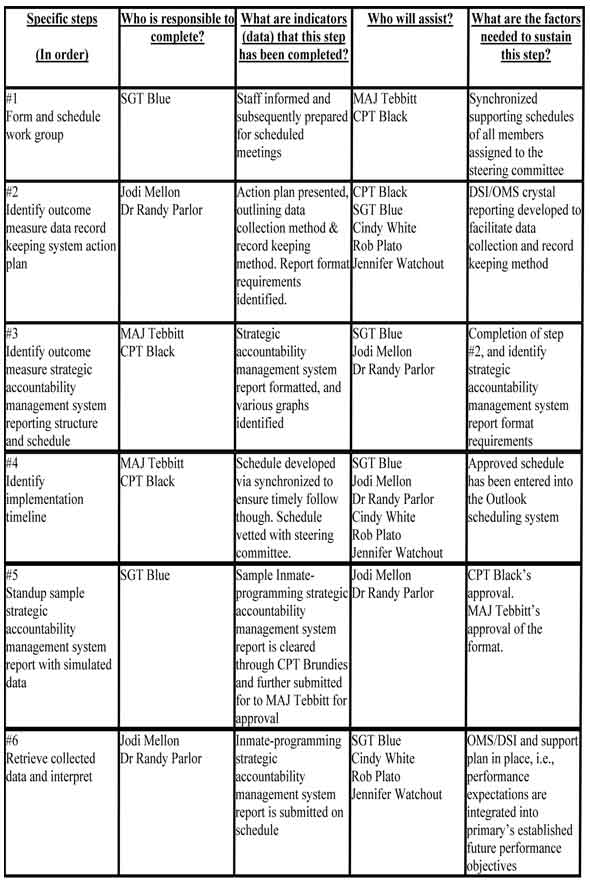

Action Planning Model Applied Although it may look somewhat different, operational planning is as important for senior executives as it is for a first-line supervisor (Yukl & Lepsinger, 2004). The vision I have for jail leadership, as the chief operating officer, is a hope that they successfully shape how the organization evolves into a dynamic inmate programming accountability environment as their management skills unfold the tenants of these six. Moreover, leaders are to use their skills to learn the art of anticipating the future. Anticipatory leaders achieve a disciplined understanding of a range of potential future conditions by using systems thinking (Savage & Sales, 2008). The kind of “systems encompassing thinking” Yukl and Lepsinger recommend within their action-planning model. Given the model as a primary means to guide problem resolution development, the Acme County jail administrator and his subordinate leadership staff analyzed the inmate programming accountability problem accordingly. As the staff started to see the future differently some amazing intelligence was discovered and the realized group’s potential enabled a new perspective within the group. The action-planning model applied to this problem initially appeared to guide process in a linear fashion. This perspective was later determined to be a bit skewed, as was revealed a pronounced set intersection of the steps. Based on the groups initial assessment work he problem was first oriented to a beginning point to an endstate within the model’s descending order, i.e., what initially appeared to be its natural flow. The group began by developing an implementation goal and associated project standards, which lead to the establishment of a formulated method to measure various existing inmate-programming participation outcomes. At this stage in the initial formulation of our action plan foundation the group reviewed a day of current inmate programming. Table #1 provides an orientation to current programming activities and outlines a usual” day’s programming participant level. From this, the grouped assembled standards to apply in support of statistical data to be collected that would support recidivism analysis, and would subsequently best represent the organizations ability to equate resource expenditure and desired outcome. Table #2 outlines provides detailed description of the adopted measures that are believed to be tailored in accordance with evidence based best practice for recidivism outcome tracking (Friendship, Beech & Browne, 2002; Hancock & Raeside, 2009). A specific focusing criterion is essential to a probable favorable program outcome and represents critical predicators of likely program success (Reinartz, 2002). The conclusion from a review of the recidivism literature and the group’s consensus, based on empirical evidence establishing industry standard studied that equates reincarceration rates with rehabilitation expenditure effectiveness. Conclusion Once the project goal and standards were established the group set to course the balance of the model’s action planning guidance. By identifying the sequence of necessary action steps for a project and establishing a timeline development stage the groups acknowledged the need to carry out each action step in accordance with a to be developed schedule. The group was tasked in the process to population a matrix supporting the models essentials, e.g., determine accountability for each action step. Table #3 provides illustration of the adopted inmate programming outcome measure action plan matrix. (See Appendix C for Figure #3), The matrix was built with minimizing forecasted potential problems and steps within the action plan will be developed to regularly review progress to determine how to avoid or minimize them. Acme County’s inmate management strategies engage programming that is either in or out of custody. The County has employed a number of alternatives to incarceration that ranges from residential to non-residential. These programs significantly contribute to the manner in which jail beds are used, and inherently act independent of the jail. Keeping this in mind, each step within the action plan details activities that will be performed by assigned staff within their respective lanes of normally assigned duties. In addition, costs associated with the computing support assessed necessary in the facilitation of tracking the program participation already exists and are available for utilization. If “crystal reporting” is required to support specific data retrieval, it is important to note that key personnel have been identified to perform this task if necessary. These two elements bear low to no additional cost for County to require allocation of any additional funds in supporting this initiative. Hence, the estimate of cost and necessary resources for each action step applied an already existing resourced organizational asset. References Friendship, C., Beech, A. R., & Browne, K. D. (2002). Reconviction as an outcome measure in research. The British Journal of Criminology, 42(2), 442-444. Retrieved from Research Library database. (Document ID: 117643485). Hancock, P. G., & Raeside, R. (2009). Modeling Factors Central to Recidivism: An Investigation of Sentence Management in the Scottish Prison Service. The Prison Journal, 89(1), 99. Retrieved from Research Library database. (Document ID: 1644103681). Kendrick, J. (Skipper). (2004). Plan or Die! Professional Safety, 49(3), 8. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 576707271). Kulisek, D. G. (2008). Ready, Aim, Fire. Quality Progress, 41(1), 75-77. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 1420662271). Kyle, N. (1993). Staying with the flow of change. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 16(4), 34. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 1287562). Reinartz, T. (2002). A Unifying View on Instance Selection. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 6(2), 191-210. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 930656941). Ritzky, G. M. (2003). Behavioral quality. Risk Management, 50(6), 56. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 353254311). Savage, A., & Sales, M. (2008). The anticipatory leader: futurist, strategist and integrator. Strategy & Leadership, 36(6), 28-35. Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global database. (Document ID: 1572045151). Yukl, G., & Lepsinger, R. (2004). Flexible Leadership: Creating Value by Balancing Multiple challenges and Choices. Chapter 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN: 0-7879- 6531-6. Appendix A: Table #1 - Program Participation  Appendix B: Table #2 - Inmate Programming Participation Outcome Measures  Appendix C: Table #3 - Inmate Programming Outcome Measure Action Plan Matrix  Editors note: Major Clifford G. Tebbitt, of the Scott County Iowa Sheriff's Office. Mr. Tebbitt is a Jail Administrator and a PhD candidate. The series includes: contemporary issues with jail/corrections administration. The series uses the fictitious County name of Acme County. Other articles by Tebbitt: |

Comments:

Login to let us know what you think

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Have you been looking for social media websites of influencers like Hamilton Lindley Facebook page? It’s got continually updated content on the best news.