|

|

| What Is Psychological Trauma? |

| By Caterina Spinaris , Michael D. Denhof |

| Published: 03/28/2016 |

The following has been reprinted with permission from Correctional Oasis: Volume 13, Issue 2.

The following has been reprinted with permission from Correctional Oasis: Volume 13, Issue 2.

In the Correctional Oasis and in Desert Waters’ work in general we frequently mention the terms “psychological trauma,” “complex trauma,” and “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder”—“PTSD” for short, often without a detailed explanation. What do these terms really mean? And to what extent are they relevant to the occupational experience of corrections professionals? To address these issues to at least some degree, we’ll be offering a series on these subjects in the Correctional Oasis during 2016. I realize that this is a very serious and possibly disturbing topic to some in several respects. At the same time, as we’ll aim to show, its reality and prevalence in corrections work necessitate that it be addressed, as lives—and definitely quality of life, health and functioning—are potentially on the line. Before proceeding any further, I want to emphasize that healing after traumatization is a distinct possibility. It is a more challenging situation when people have endured multiple traumatic exposures, but it IS a possibility, to at least some degree. Observations in wartime have shown than even the “toughest of the tough” can be affected by exposure to life-threatening events. Over the years, various terms were coined to describe the outcome of combat exposure, such as “soldier’s heart” (American Civil War), “shell shock” (World War I), “war neurosis” (World War II), “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” (Vietnam War), and “combat stress reaction” (1982 Israeli-Lebanon War). Up to fairly recently, the corrections culture of “toughness” has tended to leave the issue of occupational trauma in the corrections “war zone” unaddressed. Being “tough” is essentially a requirement for the job—especially for security/custody staff. Employees who experience or witness life-threatening incidents are burdened with the cultural expectation in their workplace that they should “get back on the horse” immediately, and continue functioning unaffected, as if nothing unusual has happened. The heavy weight of such an expectation can silence affected staff, reducing the likelihood that they will acknowledge to coworkers or even to themselves what may be really going on with them emotionally and mentally. Because of the workplace culture’s valuing of toughness, they do not want to do anything that would make them look “weak” in the eyes of their comrades. This culture of “toughness” may also contribute to their feeling ashamed for even wishing they could get some help to deal with the fallout of what they've been through or what they've witnessed. The reality however is that one of the inescapable occupational hazards of corrections work involves staff’s exposure to a variety of types of potentially traumatizing material, whether directly or indirectly. This occurs much more so for corrections personnel than for the average citizen, with the risk of suffering enduring negative neurobiological and psychological changes in health and functioning. In order to be considered psychologically traumatized, and possibly later diagnosed as suffering from PTSD, a person must have been exposed to at least one traumatic incident. So what types of incidents qualify as traumatic? Before proceeding further, we’d like to point out that the word “trauma” comes from the Greek word for “wound” or “injury.” What we are asking then is, what types of events might wound the soul (and even the brain) of those who experience them, witness them, or even just learn about them—oftentimes, over and over again? According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; 2013) [1], the criterion for what constitutes a traumatic event (diagnostic Criterion A) that can result in PTSD involves a person’s exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one or more of the following ways:

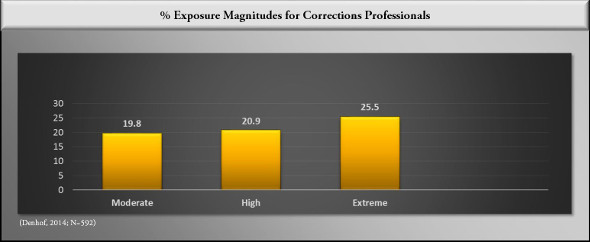

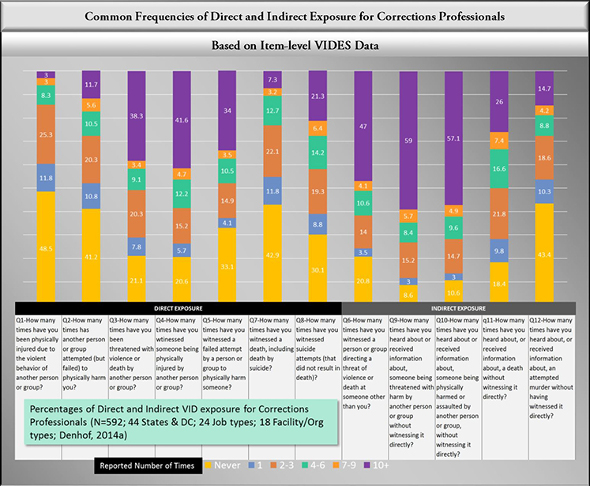

Moreover, corrections staff’s repeated or extreme exposure to death, serious injury or sexual violation indirectly through various electronic media, reports, files, videos, or pictures as part of their vocational role, is now also considered to be traumatic. So what is the research-based evidence about the degree of corrections staff’s exposure to traumatic events? According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2014, correctional officers and jailers sustained 53.5 work-related intentional injuries by another person per 10,000 FTEs. This is much, much higher than the equivalent rate for all workers (2.9 per 10,000 FTEs), and even higher than that for police and sheriff’s patrol officers (42.5 per 10,000 FTEs) [2]. From 1999 to 2008, there were 113 fatalities among corrections officers, a fatality rate of 2.7 per 100,000 full-time employees [3]. Of the fatal work-related injuries, 25% were due to homicides. Of the non-fatal work-related injuries, 38% were due to assaults and violent acts [3]. A large-sample study of health and functioning of 3599 corrections professionals was completed by Desert Waters researchers in 2011 [4]. Among an abundance of findings, data bearing on the extent of exposure to events involving violence, injury, and death were surveyed. Corrections staff participants reported having been exposed to an average of 28 distinct incidents involving violence, injury, or death in the course of their careers, including an average of 5 different types of incidents. Examples of different types of incidents to which staff reported having been exposed to on the job included offender suicide attempts, murders, physical assaults, arson, and riots. It is an established finding in research on PTSD that the likelihood of severe and entrenched PTSD increases with the number of types of traumatic incidents a person is exposed to, in addition to the frequency of exposure. An average of 28 occurrences and 5 different types, for corrections staff, reflect serious levels of exposure. To further assess corrections staff’s occupational exposure to violence, injury and death, Denhof & Spinaris designed the Violence, Injury, and Death Exposure Scale [5] (Denhof, 2014). This is a validated assessment tool in the public domain designed to assess the magnitude of exposure to work-related events involving violence, injury, or death, of a spectrum of types, and including both direct and indirect forms of exposure, and recency of exposure. Using this tool, Desert Waters researchers found that about two-thirds of a multi-state sample of corrections professionals (66.2%) scored in the moderate to extreme exposure magnitude range, with 19.8% scoring in the Moderate exposure range, 20.9% scoring in the High exposure range, and 25.5% scoring in the Extreme exposure range.  This degree of exposure can be considered highly clinically significant. It is important to also point out that this sample was not composed of only security/custody staff, who have the highest and most direct levels of exposure to work-related traumatic events; 56.8% of the sample were non-security corrections professionals. The VIDES assesses the degree of occupational exposure in relation to 12 different types of traumatic events, which are either indirect and direct in nature. When analyzed by trauma type, data collected by Denhof and Spinaris (2014) for each of these 12 types illuminates the pervasiveness of corrections staff exposure to often repeated, high stress, and potentially traumatizing events.  Click here to view enlarged. In the stacked bar chart above are percentages reflecting the extent to which a national sample of corrections staff reported having experienced particular events Never, Once, 2-3 times, 4-6 times, 7-9 times, and 10 or more times in the context of their corrections work. Yellow indicates Never and other colors indicate the percentage of staff reporting having experienced high stress events of varying types somewhere between 1 and 9 times. Notable is the pervasiveness of the color purple that can be seen from bar to bar. The color purple indicates the percentage of corrections staff who reported experiencing specific types of job-related high stress events 10 or more times during the course of their career. An average of 30% of corrections staff reported experiencing high stress events of various types 10 or more times during the course of their career. That is a very large amount of exposure. The types of events included, for example, the number of times suicide attempts were witnessed, the number of times staff witnessed a death, including death by suicide, and the number of times staff were threatened with violence or death by another person or group. Given the DSM-5’s expanded definition of the event types that can result in psychological traumatization, and given research findings on the wide extent of traumatic exposure in corrections work, it become obvious that corrections is a high-trauma occupation, like police work, firefighting, and combat military activity. The negative effects of multiple exposures to trauma over the years, and even over decades at times, accumulate and become too hard for even previ-ously healthy staff to bypass. To be continued in future issues of the Correctional Oasis. REFERENCES [1] American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (Fifth Ed.). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. [2] Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). News Release. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work. Table 14. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf [3] Konda, S., Tiesman, H., Reichard, A., & Hartley, D. (2013). Research note: U.S. correctional officers killed or injured on the job. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Corrections Today, November/December 2013, 122-125. [4] Spinaris, C.G., Denhof, M.D., & Kellaway, J.A. (2012). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in United States Corrections Professionals: Prevalence and Impact on Health and Functioning. http://desertwaters.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/PTSD_Prev_in_Corrections_09-03-131.pdf [5] Denhof, M.D. (2014). The Violence Injury and Death Exposure Scale (VIDES). http://desertwaters.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/VIDES_Data_Sheet.pdf Editor's note: Caterina Spinaris is the Executive Director at Desert Waters Correctional Outreach and a Licensed Professional Counselor in the State of Colorado. She continues to contribute to the field of corrections staff well-being individually and organizationally, in particularly regarding issues of traumatic stress due to exposure to violence, injury, death on the job, and also issues of organizational climate improvement. Michael Denhof is a Clinical Research Psychologist, Consultant, and Independent Contractor with extensive experience in scientific assessment instrument development, online data collection, psychometrics, research design, data analysis, and writing. He performs scientific and defensible measurements of behavior, attitudes, personality, health status, and outcomes, on a contract basis, and for legal, advocacy, quality assurance, or research purposes. Visit the Caterina Tudor page Other articles by Tudor: |

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Comments:

No comments have been posted for this article.

Login to let us know what you think